This post will likely be very dry, and at an extremely high view as it concerns the business of games as a commodity and how it pertains to employment, budgeting, and forecasting. Do not take me as an authority on this, rather an impassioned individual who has been burned by the lackluster business acumen of the game industry first hand. I will always defer to hard numbers which are not anecdotal on this subject.

The game industry is very much that, an industry, and an industry must profit. This is oft forgotten and overlooked because we enjoy it as an art, a sport, a social event, a tool, and a puzzle, so it comes as quite a shock when a studio shuts down. This post is not to defend any particular action, but rather to provide a little more detail to the overall financial situation of a game studio, with some topical anecdotal exploration in the conclusion.

Games are not made in a vacuum, but rather part of a larger studio budget. This budget includes the administrative staff, facilities and IT staff, HR staff, legal counsel, and the many other positions we take for granted that are part of any company. Their salaries and benefits, as well as the cost of the office space, utilities, hardware, software licenses, and more, are part of the base budget. Within that we have the game team(s), which has a similar structure but is comprised more so of the people you think of when it comes to game development.

The largest portion of any budget is the cost of the labor, and that is a factor of the local cost of living. Where your favorite game is made is a substantial factor in its profitability. The higher the cost of living, the tighter the margins, and even if a game is profitable, more work on that same scope is risky because of the location. I’ve written about this before with The Costs of Kickstarting in Expensive Cities and it still applies here, as many games are made in California, which is in general expensive.

An aside to that is the subject of outsourcing, as the reason outsourced labor is so much cheaper is typically due to cost of living differences, and in many cases, the outsource is located on the opposite side of the globe, Poland and India both being common locations, which is very convenient to tight deadlines as it allows for around the clock work on the project, though due to the difficulties of time zone differences, this labor is usually constrained to QA, art, and isolated engineering components that require little synchronization with the primary developer.

Already we are looking at a large amount of expenditures to overcome with sales of the game, but people won’t buy your game if they don’t know about it, and thus enters marketing. Marketing is never cheap, but always necessary. At a minimum, take the game’s budget, and allocate it all over again as a baseline for marketing, though it can easily go higher, say, four times as high for a large project like Call of Duty, or something akin to Blizzard’s partnership with Yum Brands. It isn’t cheap to get Soldier 76 on your large soda at Taco Bell, and the game is going to have to recoup that as well.

Why does marketing matter so much? There are two pertinent costs in any business, and those are Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Churn. CAC is convincing you to make the purchase in the first place, to dedicate your resources and time to this product and not another. Churn is the labor it takes to retain an existing customer (Call of Duty’s marketing focuses on Churn, features and content are communicated in the context of the franchise, not against other games – which makes sense as CoD hit a unique note earlier in its lifespan, gathering a large number of players who otherwise do not play video games, or only also play sports games). Customer acquisition is your baseline, and how little your customer population churns is your opportunity for franchising, and in the shorter term, microtransactions, and this is part of the push for microtransactions, as it takes action while the customer is still their customer. After you’ve purchased a game, you are willing to give it the benefit of the doubt, you want to justify your investment and are thus more receptive to additional purchases. It is far harder to convince someone to buy another game later on than it is to convince them to buy the same cash value of content within the first few months of their initial purchase. This is the opportunity to turn an expensive game into a clearly profitable one, even if sales were not great.

Then there is the question of platforms and distribution. It is a tricky road to navigate with a lot of legal and technical requirements, and there is a solution to it, a publisher. Publishers know the industry, the middlemen, the processes. They will help you get on Xbox and PlayStation, they know who to talk to at Valve, and they know a thing or two about marketing – with the pockets to make things happen. Publishers typically take 30%, and sometimes a bit of the risk (handling marketing for example is a very large investment, usually much more than what the developer was already taking on). Often the publisher guides the development with technical requirements, feature and quality expectations, and a general smell test, while reinforcing their standards with milestone payments – which are both a boon to the developer, and leverage for the publisher. It is not uncommon for publishers to acquire studios in this process, see for example, just about everyone that has come in business contact with Zenimax other than HumanHead and Obsidian.

When a studio is acquired, all of its intellectual property and debt are also acquired. This necessitates a colder and harder look at the resources in the studio, and thus usually results in fairly broad restructuring, up to and including moving the perceived talent in to other areas of the publisher, and closing down the studio. Some studios however are formed by the publisher, bringing together talent under one roof for particular goals. When they are successful, they may rename themselves to stick out in the minds of players more easily.

A game is not simply paying the studio, or the studio and the publisher, it is first paying the platforms (Xbox, PlayStation, Steam, GameStop, Target, etc) and then it goes down through the involved parties. What remains for the studio and the publisher is what helps form the operating budget, how the lights stay on and people eat. Any major variation at the beginning of that cycle and you can be looking at some scarily lean numbers for a larger project, and so safe bets are taken, franchises are revisited and rebooted, and as a last bandaid, microtransactions and lootboxes are added.

With the natural volatility of the market, and the great stakes at hand, you can imagine a studio like Raven is happy for the Call of Duty work, or Splash Damage is for the Gears of War work. They may be a rehash to players, uninteresting, but to the families of the employees, such deals are a real chance of paying off the home, and maybe not needing to move again.

That was all very high level, and non-specific, but it was catalyzed by a lot of the conversation I’ve seen around the closing of Visceral Studios by EA. There have been news stories, seemingly based completely off of a few tweets from one of the level designers on Battlefield Hardline (he was not on any of the Dead Space games) who stated that Dead Space 2 sold four million and cost $60M to make, a number he later walked back to the ballpark of $47M, based upon discussion among coworkers. We have no way of verifying these numbers, but it isn’t the sort of data point a level designer would typically have. Nonetheless, it resulted in a lot of “$60 x 4m is $240m dollars” which concluded with a harsh condemnation of EA. I am not a fan of EA, they’ve intersected with my professional life in some negative ways, but there is a bit to look closer at here.

First off, the $60 base is fallacious. Dead Space 2 did not sell 100% of its copies at full market value. Pre-orders are typically discounted, and the franchise has gone on sale many times, and Dead Space 2 in particular has even appeared on Humble Bundle. We have no idea of the marketing budget, and you can’t follow a generic rule of thumb here either, as EA was trying to establish Dead Space as a franchise with the second release. With no real measure of the game’s development budget, or the marketing budget, we cannot measure profitability.

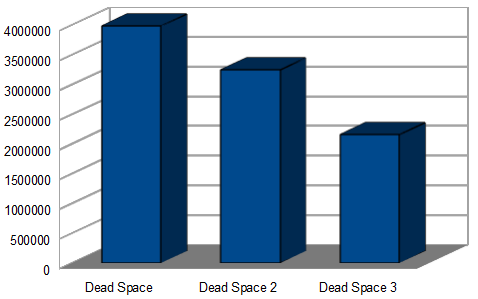

Second, Dead Space 2 did not sell 4 million copies, it sold 3.25m, he was likely confusing it with the original Dead Space which sold 3.99m copies.

Third, the first Dead Space was a serious pitch from the studio heads. Visceral was not like Bullfrog or Westwood, it was not swept up by EA but rather created by EA, and rebranded for the launch of Dead Space. This was their big shot, and selling almost 4 million copies with a new IP is excellent performance, it is no surprise that EA wanted to turn this into a franchise. The problem is, Dead Space came from within, not from EA. If enough of those people left Visceral, well, it would be a huge staffing complication to replace them, but would also endanger recapturing the magic of Dead Space. They did leave, including the studio heads who came up with Dead Space. A lot of them ended up working on Modern Warfare 3 as Sledgehammer, the following are the titles of individuals who worked on Dead Space and were later found on Modern Warfare 3:

- Executive Producer

- Senior Development Director

- Creative Director

- Audio Director

- Senior Level Designer

- 2 Level Designers

- 1 Senior Gameplay Engineer

- 1 Gameplay Engineer

- 1 Senior Core Engineer

- 1 Build Engineer

- Animation Director

- Cinematic Animation Lead

- 1 Senior Animator

- 1 Animator

- 1 Environment Artist

- 1 Assistant Environment Artist

- 1 Additional Environment Art

- Lead Visual Effects Artist

- Lighting Supervisor

- Character Technical Director

- 1 QA Technical Artist

- 2 Concept Artists

- 1 Sound Designer

That is a lot of leadership and experience to not have on hand for the sequel of the project that warranted a rebranding of the studio. Now you can argue if Dead Space 2 is on par with the original, but regardless, it did not sell as well. It sold roughly 750,000 fewer copies, and I highly doubt it was cheaper to make than the original.

Profits on an individual project are one thing, but the appearance of a downward trend is pretty scary and with Dead Space 3, well, the trend was apparent.

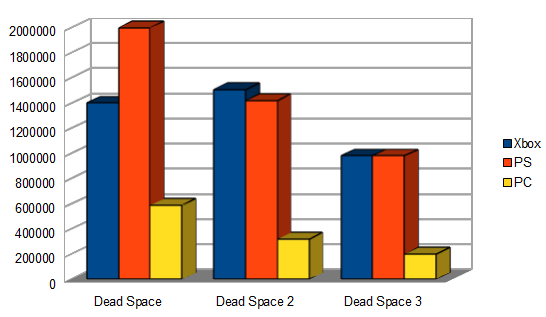

Now, Dead Space 3 may have yielded a higher profit from microtransactions, only EA knows that for sure, but it was clear, the franchise did not take hold. In fact, the only positive growth was a little word of mouth on Xbox, but that only softened the blow of sales from the original to 2.

Now, Dead Space 3 may have yielded a higher profit from microtransactions, only EA knows that for sure, but it was clear, the franchise did not take hold. In fact, the only positive growth was a little word of mouth on Xbox, but that only softened the blow of sales from the original to 2.

“In general we’re thinking about how we make this a more broadly appealing franchise, because ultimately you need to get to audience sizes of around five million to really continue to invest in an IP like Dead Space.

“Anything less than that and it becomes quite difficult financially given how expensive it is to make games and market them.

“We feel good about that growth but we have to be very paranoid about making sure we don’t change the experience so much that we lose the fanbase.”

Notice that the pivot there is to continue to invest. EA is looking at profits over time, an indication of health in the fan base that can continue to fund such a large operation. He is wary of churn, and, Dead Space has it quite clearly. Visceral’s financial viability extends into the EA general budget, which is the lifeline of the other studios, and that must be considered when you look at what you fund.

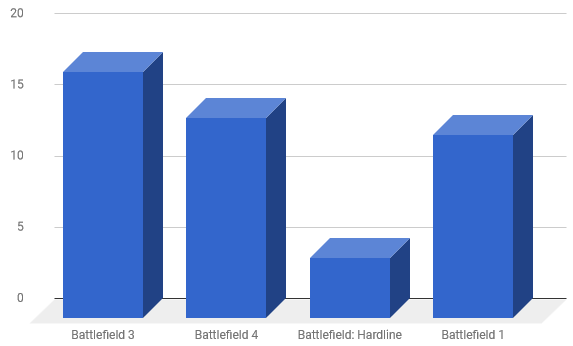

There was one big last opportunity, a shot at contributing to one of EA’s strongest franchises, not unlike what became of Sledgehammer with Call of Duty. Well…

That big dip there is Visceral. Is this fair? I do not know. What I do know is that the closure didn’t follow this. It happened recently, while they were working on one of EA’s most prized licenses, Star Wars. Chances are, they were afraid of another Hardline event, only this time it wouldn’t be with their IP, and EA goes far licensing the IP of others. As I look closer, as I remember all of my negative experiences with EA as someone who has worked in the industry, who has had their employer shut down by a parent company, I am surprised that it only just now happened, and not following Hardline.

That big dip there is Visceral. Is this fair? I do not know. What I do know is that the closure didn’t follow this. It happened recently, while they were working on one of EA’s most prized licenses, Star Wars. Chances are, they were afraid of another Hardline event, only this time it wouldn’t be with their IP, and EA goes far licensing the IP of others. As I look closer, as I remember all of my negative experiences with EA as someone who has worked in the industry, who has had their employer shut down by a parent company, I am surprised that it only just now happened, and not following Hardline.

I know the fear of sudden and large all-hands meetings, the pain of greeting your spouse with notice of some big changes in life. It may turn out that the worst thing for the employees of Visceral was the creation of Dead Space, perhaps it would’ve been better to stay with that steady stream of licensed titles. But such is the way of dreams, and such is the way of business. We all have dreams, we all require resources to get by, and what becomes of our dreams when they cost more than the needs of others who are operating within their means? When my own employer was hemorrhaging money and failing milestones, there was no sibling company I could’ve pointed to and said “Shut them down first, so that we can keep our jobs.” That parent company was less patient than EA was.

It’s a business first, and will always be a business so long as people wish to do it full time, and people wish to play them at a certain production value and with any regularity. But being a business, we do have hard figures, and as lovers of games, we can be better judges of those we frequent. EA understands that money talks, so talk to them as to how you feel about this closure, and purchase the types of games you want more of.

Apologies for how all over the board this post was, it started as high level and overly simplistic, got a bit happy with charts and finger wagging at game journalists, and then took a dive straight into industry-LiveJournal over sharing. I hope somebody learned something from it though, even if it ends up only being myself.

Excellent article; great writing style. I have a distaste for EA like a lot of people, but this really helps explain how things work with larger game studios. I can see why devs would want to stick with well known franchises which are guaranteed to make money. I can see why dream projects are scary, especially for these massive game companies. Valve in particular doesn’t seem to even be in the business of developing games anymore.